Muholi is one of the most interesting voices of Visual Activism and investigates issues such as racism, Eurocentrism, feminism and sexual politics with her works.

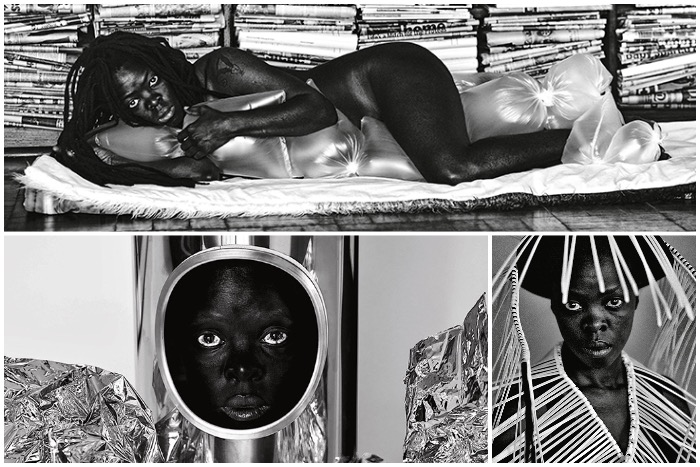

Her works are all part of a series of self-portraits that the artist began taking in 2012 and which has not yet been completed.

Her self-portraits were born out of deep pain and an urgency to denounce what is wrong. They were also recently exhibited in Italy in the exhibition Muholi. A Visual Activist.

The works of Zanele Muholi

Muholi likes to call himself an activist, even before he feels, and is, an artist.

Thanks to photography and, in particular, with his series of self-portraits Muholi has achieved worldwide success and has already exhibited in the most prestigious museums in the world.

In each of his images, there is a desire to denounce, to disturb the viewer and to communicate to the world something uncomfortable but which must be strongly affirmed.

His self-portraits are a means of affirming the need to exist, the dignity and respect to which every human being is entitled, regardless of their choice of partner or the colour of their skin, and the gender with which they identify.

BIOGRAPHY OF MUHOLI

In order to understand the genesis and observe the constantly evolving flow of Muholi’s voice, one must take a step back and trace her biography.

Zanele Muholi was born in 1972 in South Africa during the apartheid period, shaped by the violence of that regime and the bloody struggles for its abolition. He soon had to confront the violence reserved for the LGBTQIA+ community, of which he was a member. Moral and physical violence, torture often accompanied by ill-treatment and death.

For ten years Muholi fights against the concealment of the facts and photographically documents the horrors and murders of innocents, condemned because of their sexual orientation.

Muholi’s first series of artistic shots documents survivors of hate crimes who lived throughout South Africa and in townships. Under apartheid, separate townships were established, segregated ‘residential areas’ for black people who were ‘evicted’ from places designated as ‘white only’. Here violence of all kinds, including the practice of ‘corrective rape’, was perpetrated against the LGBTQIA+ community.

In the 1990s, South Africa embarked on a significant political change. Democracy was established in 1994 with the abolition of apartheid, followed by a new constitution in 1996, the first in the world to outlaw discrimination based on sexual orientation. Despite this progress, the black LGBTQIA+ community still remains one of the main targets of the most brutal violence in South Africa today.

In 2012, a particularly painful year in Muholi’s life and artistic journey, his documentary struggle comes to an abrupt end with an intimidating theft of all his unpublished files.

Muholi feels unspeakable heartbreak that, combined with the memory of all the pain he has documented, leads the artist almost to wish he were dead. It is at this moment that Muholi reacts, decides that his personal struggle must continue, but in other terms.

He turns the camera towards himself rather than towards others, thus deciding to expose himself in the first person. He renounces his own gender identity in order to represent a collective identity that gives voice to the black homosexual community through photography, and in particular through self-portraiture. The camera thus becomes for Muholi a weapon of denunciation and salvation at the same time.

« […] not many photographers like to see themselves in front of the camera. It takes me to spaces where I’m uncomfortable the most. I get to have conversations with myself in ways that I’ve never done before, which is another way of healing. »

Thus, in 2012, the art project ‘Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness’ was born, the series of photographs that Mudec decided to host in this Italian exhibition, which also became an award-winning volume; a second volume is currently being published.

Since then, Muholi has been consistently producing a series of powerful self-portraits, which captivate audiences across the board.

MUHOLI’S SELF-PORTRAITS

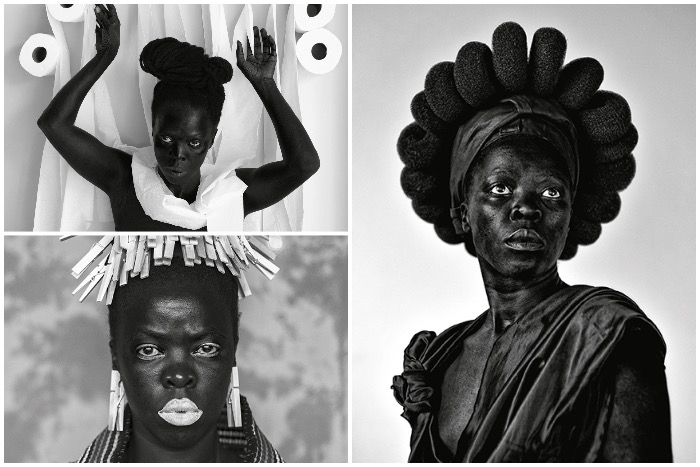

There is an underlying obsessiveness in Muholi’s art, dictated by the power of his artistic and activist message that shines through in the absolute seriality of his self-portraits, and his choice of photographic technique, in which the preparation for the shot is already an artistic performance.

Muholi chooses the setting and the light with meticulous and constant care each time, prepares the subject for the shot in a rigorous and obsessive manner, working on black and white colour contrasts, laying her body bare.

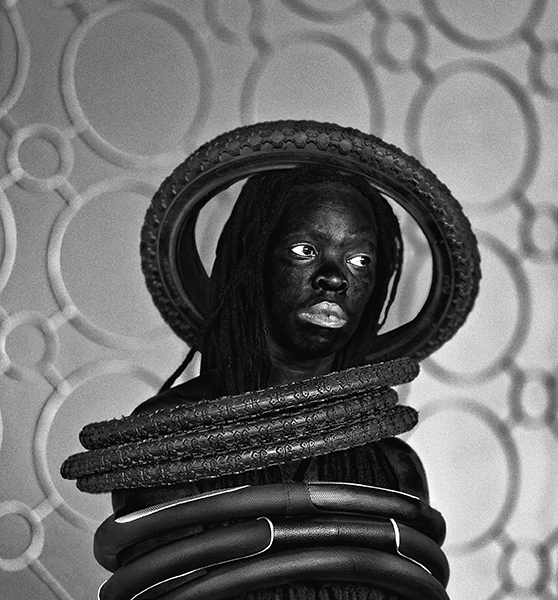

Muholi sets the stage with the surreal and metaphorical use of simple everyday objects. Headdresses made of money, necklaces made from electricity cables, clothes pegs on her head and crowns made of tyres, pliers and various strings interpreted as turbans and scarves are always used and worn on her body in surprisingly beautiful poses that often recall the fashion style of certain glossy fashion covers.

His eyes often look straight into the camera.

Through a familiar yet distorted image, Muholi invites the audience to go beyond that hypnotic gaze, to go beyond the first level of reading the self-portrait, to reflect on collective black identity, with an effect that is surprising for the evocative power of the message.

Muholi evokes exotic black Africa through the first ‘glossy’ glance, but on a second level of reading one becomes aware of the denunciation, often of the torture and ill-treatment suffered by LGBTQIA+ black communities, as in the work Ziphelele (Parktown, Johannesburg, 2016), where the use of car tyres as necklaces refers to the torture of the necklace, a method of extrajudicial summary execution carried out by clamping a petrol-soaked rubber tyre around the chest and arms of a victim and setting it on fire. The term ‘necklace’ originated in the 1980s in the black townships of apartheid South

Africa of apartheid, where suspected apartheid collaborators were publicly executed in this way.

His shots engage in an uninterrupted conversation with the world to denounce abuse, violence, injustice at every possible level. A never-ending discourse on his own emotions, on the injustice to be corrected, on the education to be offered to the new generations so that things may change, as in the shot Ntozakhe II (Parktown, Johannesburg, 2016), where Muholi’s gaze is turned forward, beyond, towards a future of hope and freedom.

In addition to the existential and autobiographical work begun with Somnyama Ngonyama, Muholi’s message of denunciation is now flanked by the gene of hope, of a path to positivity, with the thought that in the face of so much pain, the celebration of life, in all its aspects, is fundamental.

Over time, Muholi began and is still working on a second major body of images, ‘Faces and Phases’, in which she has returned to portraying the members of her LGBTQIA+ community, no longer as victims but as full protagonists of their existence, their talent, strength and beauty.

A collection that has created a strong sense of belonging in the community.

« I don’t want to say all is doom and bleak. I wanted to say that there is hope and change will come. Nobody ever thought that apartheid will be over in South Africa, it took time, yes, let me acknowledge this violence but I shouldn’t forget that there is love, yes, it’s hard it’s really hard, but thisshallpass.»

Between the end of 2022 and the beginning of 2023, Muholi decided to lose his first name (Zanele), retaining only his surname, and to continue on his personal path of self-definition, which began with the renunciation first of the gender and then of the first name, which would in any case continue to identify a singular person, coming to fully define himself only through the use of the pronoun ‘they’.

A choice that this exhibition has decided to fully endorse in its use of the most consonant language possible.

Zanele Muholi has chosen, therefore, to define itself in the plural, using their rather than he or she, but it is neither a collective nor a group of artists.

Since this society asks people to decide to belong to a gender, Muholi has chosen the non-binary one. Not she/he, but ‘they’.