Botticelli, autoritratto nell’Adorazione dei Magi

Imagine you are standing in front of a work of art, your gaze crosses that of the character being portrayed and in an instant the distance between you and the work vanishes. This powerful link between viewer and represented subject is an illusion masterfully orchestrated by artists over the centuries.

From Renaissance works to contemporary masterpieces, we discover how looking beyond the image transforms our perception of art, breaking down the barrier between fiction and reality and creating an emotional bridge that brings us closer to the story depicted.

THE GAZE IN ART

When we look at a work of art and our gaze crosses that of the character represented, it is as if the distance between us as observers and the subject represented in the work instantly disappears.

Many artists over the centuries have tried to come up with ever new solutions to make the distance between the observer and the observed ever more subtle, in an attempt to completely nullify it.

Often it is the patron who observes the viewer, or it is the artist who has portrayed himself within the work and looks into the eyes of the person to whom his creation is addressed.

THE LOOK BEYOND THE IMAGE

In the Renaissance, the invention of perspective gave artists an exceptional tool to not only accentuate the depth of space but also to make the actions performed by the protagonists in the stories depicted believable. Increasingly, Renaissance artists made a character look beyond the image to establish a direct contact between the work of art and the viewer, between the world of fiction and the concrete reality of the viewer.

That of making the gaze go beyond the image is a stratagem similar to that used by film directors, and in fact there are many works of the seventh art that use shots that act with an extremely involving effect and in which the gaze of the character on the screen voluntarily crosses that of the person observing the scene. Who does not remember the gaze of the protagonist in Stanley Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’, which cancels the distance between filmic fiction and reality.

In Masaccio’s Trinity, the Virgin is depicted at the foot of the cross, but her gaze is directed towards the faithful who are observing and at the same time she points with her right hand to her crucified son as if to communicate a request to share her own pain, or to invite prayer.

Raffaello, Madonna Sistina

FROM FICTION TO REALITY

The crossing of gazes between the observer and the observed, between image and reality, creates an emotional bridge between the story and the viewer. In theatre jargon, the abolition of this barrier is called the abolition of the ‘fourth wall’, i.e. the elimination of that element that separates representation from real life.

In Filippo Lippi’s Madonna and Child with Two Angels, the illusionism of the fake stone frame framing the scene is accentuated by the figure of the angel in the foreground who, while supporting the infant Jesus, finds time to turn his gaze towards the observer, capturing him with a smile and an almost winking look.

Raphael’s Sistine Madonna is Pope Sixtus IV pointing to the Madonna with his right hand, which is us observing. There is also no lack in this work of the gazes of Mary and her son who look beyond the painting, seeking contact with us and indeed advancing towards us, walking on a carpet of clouds. Moreover, the two famous little angels, somewhat bored and leaning on a sort of windowsill, accentuate the feeling of continuity between the inside of the work and what lies outside, that is, on this side of the work.

THE ARTIST AS AN EMOTIONAL BRIDGE BETWEEN THE WORK AND THE VIEWER

From the 14th century onwards, a variant of the viewer’s gaze was introduced and the inclusion of the artist’s self-portrait in the work of art became increasingly common. This was an important awareness on the part of artists, who acquired a new awareness of their social and cultural role, the result of an emancipation from their previous status as artist-artisans.

For an artist to insert his or her own self-portrait within his or her work, looking at the viewer, is to send an invitation to the viewer to participate in the story depicted, moreover it is the proud claim of authorship of that work.

Famous is Sandro Botticelli’s self-portrait in the Adoration of the Magi, in which the artist has painted his own full-length portrait on the right-hand margin of the image, giving his face a smug expression and a gaze that seems to be leaving the scene.

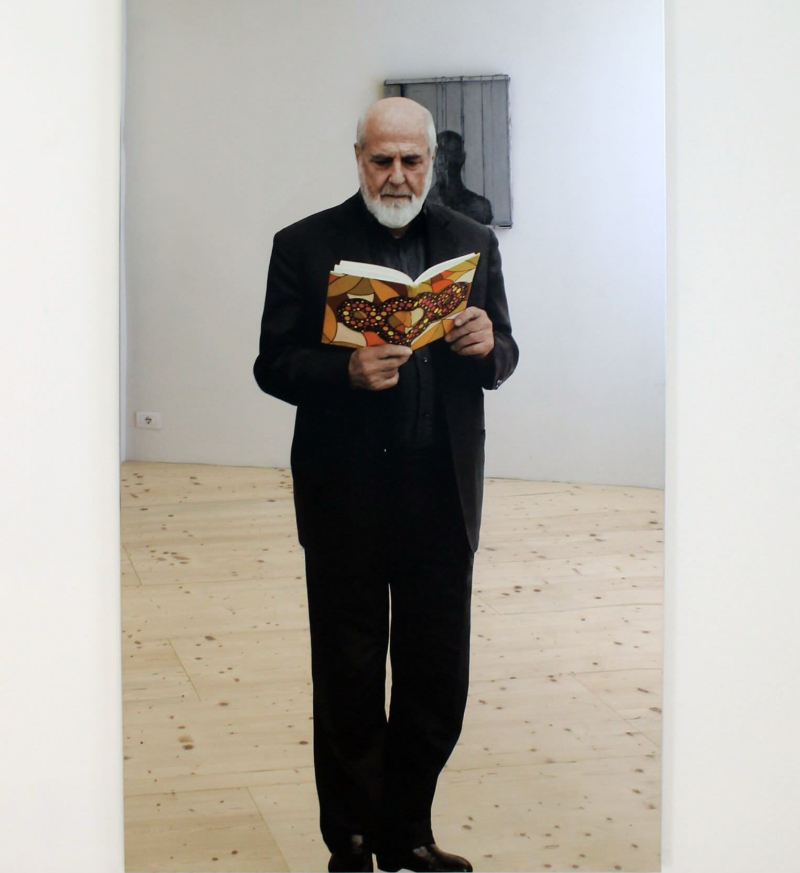

Despite the experimentation and abstract direction of contemporary art, even 20th century artists did not shy away from the desire to portray themselves within their works. Starting in 1960, Michelangelo Pistoletto developed a new typology of the self-portrait, applying the image of his own life-size figure on mirrored surfaces, creating a sensational result: on the one hand he crosses his own gaze with that of the viewer, on the other hand he draws the viewer into the work through his own reflected image.

Fiction reality overlaps and starts a dialogue.

Michelangelo Pistoletto autoritratto specchiante

The gaze in art is more than just a detail, it is a powerful means of connection that transcends time and space. Through this interplay of gazes, artists invite us to become part of their creation, involving us emotionally and intellectually. Whether it is a Renaissance fresco or a contemporary work, the silent dialogue between the viewer and the work of art continues to evoke wonder and reflection, reminding us that in the contemplation of art, reality and fiction are inextricably intertwined.