Raoul Dufy (1877-1953). “30 ans ou la vie en rose”. Huile sur toile, 1931. Paris, musée d’Art moderne.

EXPERIMENTATION AND COLOUR IN THE WORKS OF RAOUL DUFY

Raoul Dufy was born into a humble family of modest economic circumstances.

His father was an organist and passed on his passion for music to his son Raoul, which the artist cultivated for the rest of his life and transferred into his works.

In Raoul Dufy’s works there is experimentation and colour, a constant desire to communicate through light and through what life had in store for the man who was one of the greatest interpreters of art history, straddling Impressionism and Fauvism.

The works of Raoul Dufy

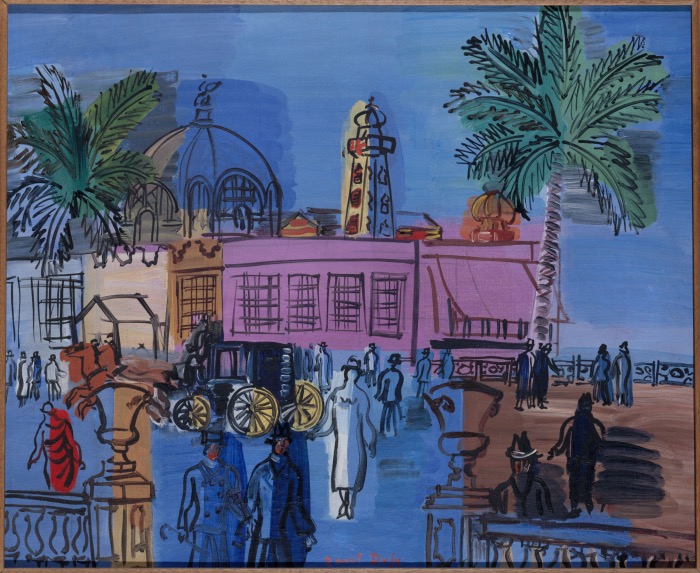

Raoul Dufy (1877-1953). “La Jetée, promenade à Nice”. Huile sur toile, 1926. Paris, musée d’Art moderne.

Raoul Dufy was the creator of monumental works such as the monumental ‘La Fée Electricité’ (The Electricity Fairy, 1937 – 1938) preserved at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris. One of the largest paintings in the world, with a total length of 6 metres, it consists of 250 panels and was commissioned by the ‘Compagnie Parisienne de Distribution d’Électricité’ to be exhibited in the Electricity Pavilion at the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris.

Thanks to his ability to capture atmospheres, colours and the intensity of light and to transfer them onto his canvases, he became the painter of joy and light. Able to experiment right up to his last work.

Due to a family financial crisis, in 1891 the young Raoul was forced to look for work in Le Havre, a particularly stimulating environment that brought him closer to two masters of Impressionism such as Monet and Pissarro and that later, in 1905, led him to the more modern painting of Matisse.

1903 was the year of his first appearance at the Salon des Indépendants, where he exhibited until 1936 and was then accepted in 1906 at the Salon d’Automne (until 1943).

His artistic activity from then on was uninterrupted and, from 1910 onwards, he expanded his activity in the field of decorative arts, successfully establishing himself in a vast production, from woodcuts to paintings and graphics, from ceramics to textiles, from illustrations to stage designs.

RAOUL DUFY AND CÉZANNE

Raoul Dufy was an exponent of the movement that drew on the great names of post-impressionism, Van Gogh, Gauguin and especially Cézanne, who played a major role in the artistic avant-garde.

Georges Braque and Dufy knew each other and together painted the same sites loved by Cézanne, skeletal and angular trees, cubic houses, sketched bays. Together they create compositions with a reduced colour range and characterised by a certain austerity, until Dufy returns to Paris and discovers colour.

RAOUL DUFY AND ENGRAVING, BOOKS, FASHION AND DECORATION

Raoul Dufy made his first woodcuts in 1907 to illustrate a collection of poems by Fernand Fleuret (Friperies, published in 1923) and then Guillaume Apollinaire’s Bestiary or The Courtship of Orpheus (published in 1911), a work that Picasso had refused to work on.

Dufy was inspired by medieval bestiaries and created images that were a masterpiece of inventiveness, playing on the contrasts of black and white.

From 1925 onwards, he also reproduced the picturesque atmosphere of the cities of southern France by illustrating books such as Gustave Coquiot’s La terre frottée d’ail, Eugène Montfort’s La belle-enfant o l’amour à quarante ans (1930) and The Prodigious Adventures of Tartarin of Tarascona (1937).

Rural landscapes, bouquets of wild flowers, scenes of rural life, still lifes in the garden, are the main themes of these works executed in watercolour.

It was at the end of 1910, however, that he met the fashion designer Paul Poiret, a great admirer of the Bestiary woodcuts, who proposed to Dufy that he set up a craft workshop for printing on fabric, the Petite Usine.

Dufy transposed the technique of woodcuts into textiles, studied all stages of production with the help of a chemist, and designed sumptuous printed fabrics for fashion and furniture for the Poiret fashion house.

This first success earned Dufy an engagement with the Lyon silk mill Bianchini-Férier from 1912 to 1928. He adapted his textile creations to industrial production and drew on his favourite motifs in that sphere: flowers, including the rose; animal and exotic patterns; the sea and mythological subjects; but also Paris, contemporary life and sport; and finally abstract and geometric decorations whose real protagonist was colour itself.

This activity led him to create the fourteen monumental wall hangings that adorned the Orgues barge at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts.

Given their quality and creativity, these decorations, whose gouache sketches are true works of art in their own right, are fully inscribed in the Art Deco current and contribute to the development of Dufy’s style, realising throughout his career an extraordinary alliance between painting and decorative art.

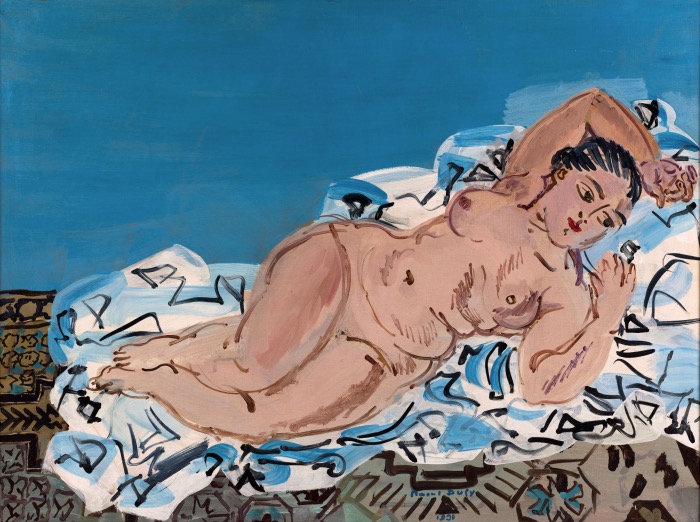

Raoul Dufy (1877-1953). “Nu couché”. Huile sur toile, 1930. Paris, musée d’Art moderne.

THE BATHER BY RAOUL DUFY

Raoul Dufy’s work is studded with memories of his childhood spent in Le Havre, including the bather observed on the beach at Sainte-Adresse, which in his eyes represents “the first revelation of plastic beauty”.

Dufy transformed the figure of the bather into a central and recurring iconographic motif in his works, declining it in an infinite number of variations.

Dufy’s Bather is enriched with a mythological and allegorical dimension through the reference to the figure of Amphitrite, who appears in Dufy’s decorative repertoire in 1925, following his trip to Italy and the discovery of ancient sites in Sicily in 1922. But references to Botticelli’s Venus can be glimpsed, and this figure will also return in the cups, majolica tiles and vases made from 1922 onwards with the ceramist Josep Llorens Artigas.

There is no bather without the sea and Raoul Dufy never ceased to depict seascapes, from Normandy to Provence.

His love for the sea, ports and resorts was his first source of inspiration and dominates all his work. He is fascinated by the spectacle of nature, the intensity of the light and its reflections on the water, the expanse of the panoramas, as well as the animation that characterises the leisure venues of good society in the inter-war period.

RAOUL DUFY IN ITALY

From March to May 1922, Raoul Dufy travelled through Italy, visiting Florence, Rome, Naples and then Sicily.

Although he did not paint views of Italian cities, he was impressed by nature and produced some twenty paintings inspired by that trip, in which the Mediterranean light allowed him to simplify his colour palette.

To reproduce vegetation, he resorts to arabesques and squiggles while preserving the structural appearance of the trunks. He proceeds in the same way to depict clouds, roof tiles and the sea. All these signs will become identifying elements of his style.

Here is what Dufy wrote during his stay in Sicily:

“I am in the mood of one of those English hedonists who have travelled a long way and bore us with tales of their wanderings. I am in Port Ulysses, I am thinking of Homer.”

RAOUL DUFY, WHEAT, HORSES AND MUSIC

There is nature in the works of Raoul Dufy but, from 1910 onwards, there are also the seasons and work in the fields.

Wheat sheaves became part of his decorative repertoire from 1919 and in the 1930s he dedicated a series of paintings to wheat fields, referring to Van Gogh, a master he admired.

Fame, however, came with the scenes depicting horse races in the 1920s and 1930s.

The works inspired by the world of horseracing are populated by models and elegant ladies dressed in the clothes of great stylists, by jockeys in multicoloured tunics and by all those characters that revolve around the world of racecourses.

From 1923 to 1924 he painted the French racecourses of Deauville, Chantilly and Longchamp and during his stays in Great Britain, from 1930 to 1932, those of Ascot, Epson and Goodwood.

Compared to Edgar Degas, it was not so much the horses, the jockeys or the movement that interested him, but the whole spectacle of racing in a dazzling synthesis of colours. Taking great liberties with perspective, he paints subjects out of scale to enhance their importance and neglects details instead.

Music, he who was born into a family that lived off musicians, is not missing from his works.

From the very beginning he expressed his passion for that art with the Orchestra of Le Havre in 1902, followed by Homage to Mozart in 1915. Those canvases were the prelude to the numerous representations of orchestras, quintets, ballets, still lifes with musical instruments and tributes to great composers such as Mozart, Bach and Debussy that illuminated his work in the 1940s.

In the 1910s, Guillaume Apollinaire introduced the artist to literary circles and Dufy began to frequent the exponents of the musical avant-garde and to design stage sets.

During the war years, music took on a predominant role, he improvised private concerts in his studio, attended the municipal theatre and attended sardana and carnival performances.

He transposes that atmosphere into his painting and portrays symphony orchestras and concert performers in action. He creates imaginary visions in which music and theatre mingle through the figure of Harlequin, emblem of the commedia dell’arte and the Venice carnival, which he discovered during his first stay in the city of the doges in 1938. The favourite subject of numerous painters, from Cézanne to Picasso, this multi-faceted character inspired him from 1939 to 1946 with a series of Harlequin musicians.

RAOUL DUFY AND THE ELECTRICITY FAIRY

The Electricity Fairy (La Fée Electricité) is “the largest painting in the world”.

Conceived and realised by Raoul Dufy for the Light and Electricity Pavilion, for the ‘International Exhibition of Arts and Techniques in Modern Life’ in Paris (1937), it was completed in just eleven months.

The artist’s brother Jean Dufy was in charge of the scientific documentation, assisted by an expert, but the artist himself took notes and met with some scientists.

The painter works on 250 plywood panels measuring 2 x 1.20 metres and, in a disused factory that serves as his studio, he sets up a real construction site. Once painted, the panels are screwed onto a metal frame.

Dufy chose to use Maroger colours (‘resinated oil, emulsified in gummed water’) because of their short drying time. The pliability and transparency of the paint make it resemble watercolour. In addition to a 1/10 scale study, the painter produces numerous drawings, watercolours, drawings on tracing paper, which he uses to trace on panels the outlines of shapes photographed on glass plates and then projected, with a magic lantern, at the desired scale.

Like a kind of symphonic poem, this large “poetic, historical and pictorial” decoration evokes the observation and invention of electricity by scientists and inventors, arranged in a frieze from antiquity to the present day, and the effects of their discoveries on daily life and the progress of humanity.

The artist inserts small narrative episodes inspired by the technique of photomontage, fits the stories into one another, and modifies the scales, suppressing perspective and the horizon. He uses large swathes of colour to visually link the scenes to one another.

Raoul Dufy (1877-1953). “Régates aux mouettes”. Huile sur toile, vers 1930. Paris, musée d’Art moderne.

THE ROLE OF DUFY IN ART HISTORY

Often misunderstood due to the apparent simplicity of his pictorial style, Raoul Dufy actually had a complex and articulate education, which led him to experiment throughout his life.

Initially influenced by Impressionism, he later approached Fauvism, drawing inspiration from the figures of Matisse, Braque and Cézanne. Dufy’s particularity lies in gradually dissociating colour from drawing over the course of his artistic maturity, simplifying as much as possible and thus putting form before content.

Throughout his artistic career, he followed the theory that colour serves painters to capture light and illuminate their works.

Dufy was an artist in perpetual search of stimulation and experimentation, able to make art that was committed but at the same time light.