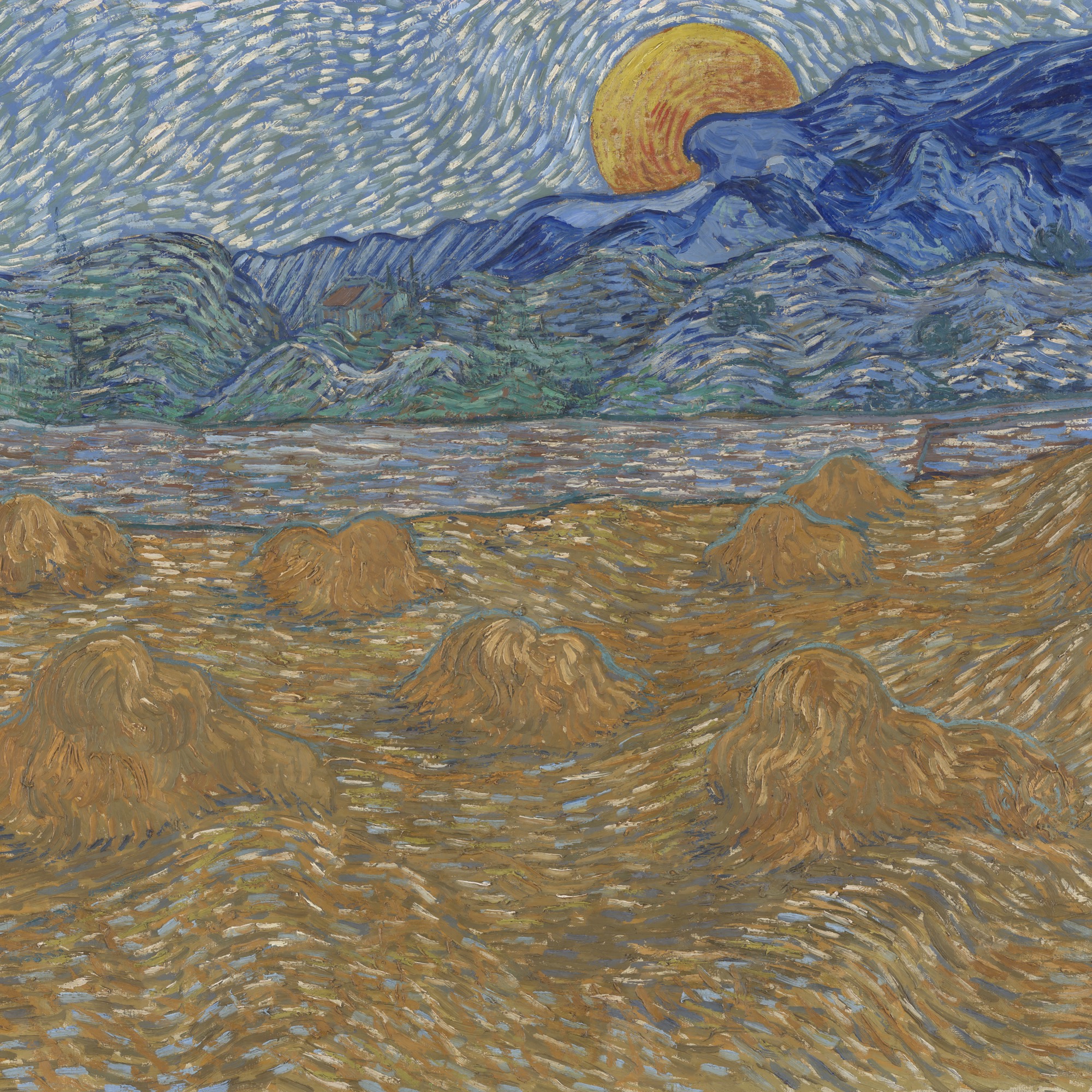

Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon

It was 8 May 1889 when Vincent Van Gogh asked to be admitted to the asylum at Saint-Paul-de- Mausole.

It was a conscious choice on his part because he realised that he had to change something in his life and in his mind. His is an extreme desire to regain a serenity he has lost or, more likely, never known.

When the doors of the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum open for him, he begins a journey to try to find serenity and balance, but he continues his work as an artist.

Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon

THE LIFE OF VAN GOGH AT THE SAINT-PAUL DE MAUSOLE ASYLUM

Van Gogh’s stay at the Saint-Paul de Mausole asylum is not easy.

The artist’s days are spent in isolation from society and in contact with a reality made up of screams and patients who constantly manifest their mental instability.

As always happens in van Gogh’s life, it is his brother Theo who comes to his aid and provides him with a room in which to paint, on the first floor of the building.

For a year, the room in the asylum where he was allowed to paint became his studio.

It is a room lit by sunlight that penetrates through a single window, to which Van Gogh looks out every day. The view that Vincent can admire from that one spot becomes the dominant subject of the works produced during the months he spends in the asylum. The same wheat field, painted at each change of season, at different times of day, becomes almost an obsession for him.

ANALYSIS OF VAN GOGH’S LANDSCAPE WITH SHEAVES AND RISING MOON

The landscape van Gogh painted is what he saw every day from the window of his room at the asylum to which he had committed himself.

There are at least ten versions of that cultivated field, all different and all unique.

At the beginning of July 1889, he painted Landscape with Haystacks and Rising Moon, where he took up a sketch he had drawn in a letter to Gauguin:

“I have one in preparation for the moonrise on the same field as the sketch in Gauguin’s letter, but sheaves replace wheat. It is dull ochre yellow and purple […]’.

The earth comes alive, transforming itself into a moving surface on which the volumes of the sheaves echo the soft slopes of the hills and the crevasses of the mountains.

We are at sunset, the moon is rising behind the mountains and the wheat is tinged with orange, the violet tone of the mountains already hints at a nocturnal landscape, the touches of the brush are still influenced by the language invented by the Impressionist painters, to which Van Gogh felt intimately attached.

Just as in Monet’s works, Vincent records the changing light and colours of the same viewpoint over the course of days and seasons.

For months he tirelessly describes the field enclosed by a dry stone wall with the mountains in the background, only changing the time of day or adding some small detail: dawn, dusk, evening, sometimes he inserts a reaper. Incredibly, in his most mentally unstable period, he manages to carry out an extremely rational artistic project.

He plans his work sessions, studies colour effects and calculates the gestures to be made on the canvas.

Landscape with Haystacks and a Rising Moon, which is part of the Kröller-Müller Museum’s collection of works in Otterlo, is proof that Vincent never painted in the grip of his psychotic crises, but used his rare moments of lucidity to compose masterpieces of clear Impressionist inspiration, thanks to his pained brushstrokes that mark the path towards Expressionism.

INSPIRATION FROM VAN GOGH

In a letter to his brother Theo Vincent confesses:

“[…] through the iron-barred window I can glimpse a square of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective in the manner of Van Goyen, above which I see the sun rise in its splendour in the morning”.

Van Goyen was a 17th century Dutch painter, a Baroque artist and a specialist in landscapes without human figures. In his works he used muted colours to reproduce the rarefied atmospheres of Northern Europe.

With this reference van Gogh shows us that, even though he was in an asylum and going through one of the hardest periods of his life, he did not give up reflecting on the history of art. His work does not stop and, on the contrary, he continues to compare himself with the masters of the past, placing his work in the groove of a noble tradition.

Follow me on:

About me

In this blog, I don't explain the history of art — I tell the stories that art itself tells.