CLAUDE MONET, Vue de Londres dans le brouillard “La Tamise”. Tecnica mista su carta. 21×28 cm . 1903. Collezione privata

THE REVOLUTION OF IMPRESSIONISM: EXPERIMENTS AND SUCCESSES

When, in April 1874, a small group of artists organised an exhibition at the studio of the photographer Nadar in the Boulevard des Capucines in Paris, they did not think they were at the beginning of an artistic revolution. It was the debut of a group of young artists who were about to create an unprecedented artistic phenomenon.

The curator of the Impressionists between dream and colour exhibition, Vincenzo Sanfo, explained well what the Impressionist revolution consisted of and emphasised how from the dismay and horror with which the first works were greeted, we moved on to …

The Impressionism Revolution

LECOMTE PAUL, Paris. Olio su tela, 55×48 cm 1842/1920

Here is what Vincenzo Sanfo writes, starting with the first exhibition of Impressionism, which took place in Nadar’s studio.

One of the paintings on display, Monet’s ‘Impression, soleil levant’, was quoted by Louis Leroy, a critic of the time, who paraphrased the title and created the term ‘Impressionist’ painting, which remained from then on as indicative of their style and, in fact, became synonymous with a way of painting.

More than a century and a half after that exhibition, the success of these artists does not cease to spread and propagate, despite the succession of fashions, modernisms and cultural revolutions.

The triumphal march of the Impressionists continues unabated. To what do we owe this success? Their undisputed supremacy in popular and collectors’ favour?

Undoubtedly a large part of it is due to the sincerity of their painting and the intrinsic ‘Joie de vivre’ they instilled, with their use of light in warm, radiant tones. But what particularly strikes one whenever one contemplates a work by the Impressionists is certainly, beyond the seduction that emanates from their paintings, the unconscious nostalgia for a world now lost and of which the Impressionists were the main singers.

Divided into two currents, stemming from Daumier and Millet, the experiments of Pissarro, Manet’s Goyesque reinterpretations and Renoir’s research would thus begin, leading to surprising results, in part decanted into the formal innovations of one of the greatest experimenters of graphic techniques and printed reproductions ever to appear in the history of art, Toulouse-Lautrec.

Vincenzo Sanfo emphasises how fundamental to the Impressionist movement were the experiments in engraving and graphic techniques, which led to the creation of works that changed forever, with their acrobatic inventions and manipulations, a medium that had become repetitive and banal.

The Impressionists contributed to making engraving techniques a new and autonomous art, incorporating retouching, highlights and other interventions that made them not serial works of reproduction but practically unique pieces.

And Vincenzo Sanfo continues in his essay with some concrete examples.

In particular, Degas devoted himself to the masterly use of the monotype technique, where he consigned extraordinary and unique works to the history of art, most of which are now preserved in the National Library of France. Some of these monotypes are known thanks to Ambroise Vollard, who edited two splendid volumes, La Maison Tellier and La Famille Cardinal, in which Degas’ monotype technique is faithfully and, rightly, highlighted.

And Degas actually wanted his monotypes to be the basis of his first and only solo exhibition, which he organised himself and which, contrary to what one might expect, did not include dancers and portraits, but stunning landscapes, created with the pastel and, indeed, monotype technique.

Landscapes, some of which are still unknown to the general public today, and which were created practically from life during a long train journey, in which he fixed the flow of the landscape, which he saw from the window and brought back as if in a sort of fading image, with a cinematic tone, with a result that well resembles the informal disintegration of Monet’s water lilies and certain tender and evanescent landscapes of Renoir’s later years.

Engraving techniques became, for many of the Impressionists, the most intimate and private field in which to study, experiment and take notes, which would later, to some extent, enter into painting and offer insights and reflections, as for example for Monet.

In fact, to demonstrate how true this is, one only has to compare Monet’s iconic work, the painting ‘Impressions, soleil levant’ to clearly see the reference to Jongkind’s engraving ‘Soleil couchant Port d’Anvers’, made by the great Dutch painter as early as 1868 and which Monet, after seeing it, made his own through the painting that became historical and fundamental to universal art and that unknowingly gave its name to the Impressionist movement.

This indicates the extent to which engraving techniques were not subordinate to Impressionist painting, but rather constituted a separate, autonomous and independent corpus, and were often themselves the inspiration and mother of much painting in the late 19th century.

Pissarro, for example, in his conspicuous graphic production of over two hundred engravings and lithographs, never reproduced any of his paintings on his plates, if anything he did the opposite, using his engravings as traces for them.

For many Impressionist artists, that of graphic techniques was a world of its own, to which they reserved ideas and experiments, confident of the originality and possibilities that the medium could give them, especially in the monkish severity of the sign and black and white, to the point of making Degas say that engraving was “one of his greatest joys as a creator”.

ÈDOUARD MANET, Portrait de Berthe Morisot. Héliogravure da litografia. 16,5×23,5 cm. Litografia del 1872. Ed. 1939

But Vincenzo Sanfo goes on to emphasise how the Impressionists’ experiments in the field of graphics occurred in the period before the Impressionist revolution. It was a period of study to find new creative outlets, even before commercial ones, and Oriental art played no small role.

Indeed, Vincenzo Sanfo continues by stating:

All Impressionist art, and in particular the art of engraving, nevertheless owes a great debt to Oriental art, which was already known in the time of King Louis XV thanks to the important collection of Chinese books and drawings that belonged to the collection of Bertin, the former controller of the King’s finances.

This collection was later confiscated by the French Revolution and fortunately became part of the collections of the National Library of France, together with that on Japanese art, where they still constitute the most important repository on Oriental art in Europe.

Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, for example, were regular visitors to the Cabinet des Estampes of the National Library and from these frequentations they drew inspiration and used it to spread a taste for composition that found, even in many artists of the time, precise correspondence, leading to an evolution of compositional taste that, precisely from graphic experimentation, then moved on to painting and the applied arts.

For artists such as Monet, Bracquemond, Henry Somm and many others, the works from China and Japan were an endless source of inspiration and served to give rise to a new style of painting, which would flow from Impressionism to Symbolism and even Art Deco.

In particular, the works from the Oriental collections were fundamental to the birth of modern advertising, as well as to all graphic art in the centuries to come.

L’eredità di artisti come Corot, Millet e i compagni dell’Ecole de Barbizon, intrecciata con le esperienze grafiche provenienti dalla Cina e dal Giappone furono la base di un mix di espressioni che trovarono proprio nel mezzo della grafica una autonoma capacità di ispirazione e servirono a dischiudere nuove strade alla pittura impressionista.

It is also curious and emblematic to note how an artist such as Manet, who, although close to the Impressionists, never participated with his paintings in their exhibitions, instead participated out of solidarity in the first exhibition held by Nadar in 1874, with a series of engravings, including the ‘Dead Bullfighter’.

By the way, this engraving, as well as his other works, were made well before the birth of Impressionism and therefore far removed from the feeling of that movement, being closer to Italian and Spanish art than to the dictates of the nascent Impressionism.

For Renoir, on the other hand, the creation of graphic works is much later than the fateful 1874 and therefore the birth of Impressionism, as his first graphics date back to 1889 and were mainly dedicated to the market, before being used for research, serving as illustrations or as accompaniment for works commissioned by skilful and capable dealers, such as Ambroise Vollard or Durand-Ruel, who saw in the renewed vitality of graphic art a new and rapidly expanding market.

A typical example of this vision is the much sought-after portrait of Wagner, commissioned from Renoir specifically to be marketed, given the popularity of both the great composer and Renoir himself, who in truth devoted himself mainly to lithography, not disdaining however the drypoint technique, which allowed him those formal arabesques that brought him closer to his painting.

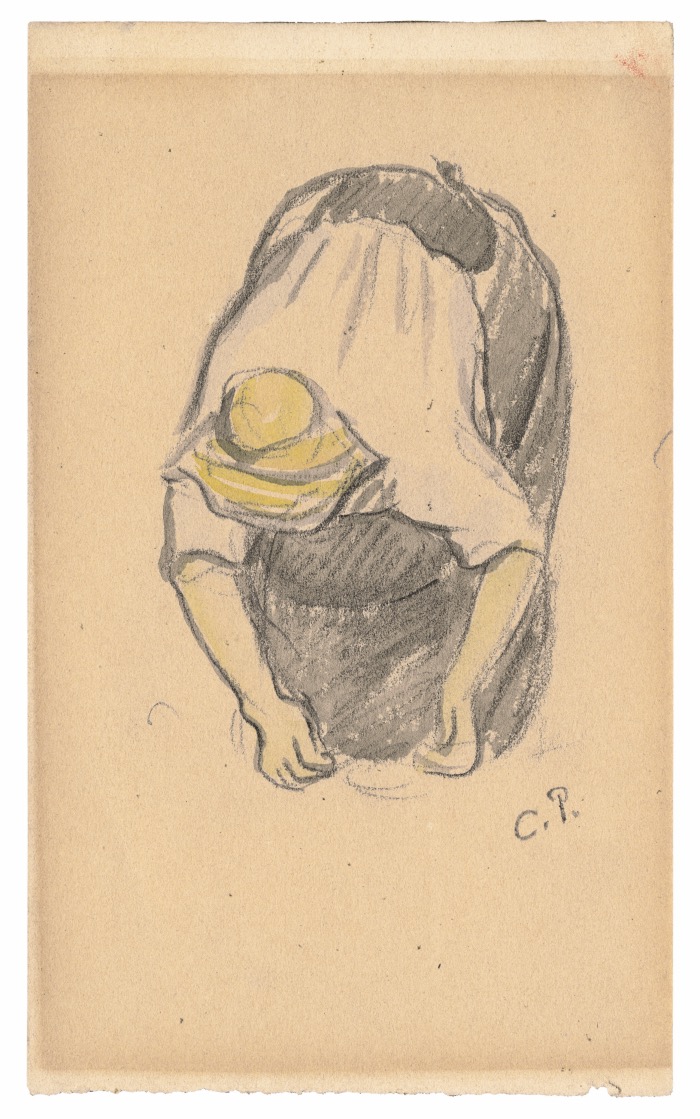

CAMILLE PISSARRO, Femme Accroupie. Tecnica mista su carta. 15×10 cm. 1882-1883. Collezione privata

Vincenzo Sanfo also dwells on the work of Gauguin, who took part in many Impressionist exhibitions, also organised them himself, and who produced lithographs summarising his pictorial experiences to finance them. Works that, among other things, he used as an outline to create the series of woodcuts during the years of his Polynesian refuge.

If from the Impressionist adventure and its experiments, graphic art will find new outlets and new sources of inspiration, Sanfo invites us not to forget that Impressionism is also life ‘en plein air’, the woods around Paris, Barbizon, Fontainebleau, Louveciennes and the Seine and its haunts. Impressionism was above all a cultural revolution that brought together artists so different in style, character and training but who renewed art and led it towards full freedom of expression.

What is left of the Paris that cradled, inspired and formed the Impressionists?

Vincenzo Sanfo also provides an answer to this question.

Very little is left of that Paris today, and anyone wishing to retrace its steps would find it difficult to recognise the streets, houses and studios immortalised in the famous canvases. Only Delacroix’s studio has remained almost intact, in the splendid Place Fűrstenberg, testifying to what life must have been like for a painter at the birth of the movement.

The great Haussmannian demolitions and the constant transformations the city underwent meant that even the Cirque Ferdinand, which could still be seen in recent times, was demolished in 1972, as was Nadar’s legendary studio, recently razed to make way for an anonymous building. To breathe in some of that Bohemian air, you have to go up to Montmartre, where some places are still preserved, such as the Moulin de la Galette, the Villa des Arts, which housed the studios of Renoir, Cézanne, Signac and then Utrillo and his mother Suzanne Valadon.

The last vineyard still stands today, which, albeit in small quantities, continues to produce the famous Montmartre wine, and in the days of low tourist density, very few in truth, it is still possible to breathe in that small village air that enchanted a generation of artists, becoming their refuge and inspiration, a place of the soul and of perdition, so much so as to become the myth of an era long gone. Of all the rest, nothing remains, and one has to travel outside the city to still discover the places of one of the most extraordinary revolutions in the history of art; one has to go to Fontainebleau, where the forest has remained almost unchanged, or to Barbizon where it is still possible to visit the houses that housed Millet and his friends and some of the inns made famous by that handful of young painters. Other places that restore part of that lost world are Louveciennes, where Pissarro’s house still stands, and above all Giverny, where Monet lived and in whose house the atmosphere that inspired some of the master’s most famous masterpieces is still intact.

The architectural and social transformations that swept through France in the late 19th and early 20th century and the advent of new technologies such as photography and film helped to accompany the Impressionist revolution, which had to take into account the new demands, which arose from a vision of the image that could no longer be relegated to a pure narrative of epic or mythological gestures, but was obliged to represent the reality of a new world, with the predominance of new figures, emerging from the frenetic transformations and the incessant pulsation of hitherto unimaginable activities and commerce.

The Impressionist revolution bore witness to all this and, while proposing an archaic and idyllic world, it did not ignore the power of the new, gigantic railway stations, the appearance of the first automobiles, the appearance of flight and the teeming fervour of its boulevards.

Paris also turned into the city of pleasure par excellence, with its numerous cafés, cabarets, theatres, circuses and famous brothels that became, on the whole, a source of inspiration for many artists, who immortalised these themes that were particularly congenial to them.

It was therefore easy to see Renoir, Degas and their companions in the foyers of the Opéra as well as in the ‘maisons closes’ or in the Moulin Rouge’s redoubt which, opened in 1889, would become the temple of transgression and invent – as well as a new dance, the French Can Can – also a new method of advertising, relying on the posters of Toulouse-Lautrec, which, supplanting those of Cheret and Steinlein, would fill Paris with new and daring images with completely innovative graphic approaches and initiate a new system of communication, giving rise to modern advertising.

The construction of the Eiffel Tower at the Universal Exhibition of 1889 will mark the culmination of a social as well as artistic revolution, and nothing will ever be the same again. Rural and peasant civilisation will be supplanted by urban and industrial civilisation, and in the world of art, the road paved by the Impressionists will become wider and wider, giving rise to a generation of new artists, free to create and desecrate.

The witness of this transformation, which rests on the foundations of Impressionism, will be a young and talented foreigner, who will steal what still remains of the spirit of an era and will immortalise the last absinthe drinkers, the mature models, the derelicts, strangers to a society, in the race for economic and social well-being. He operated a reinterpretation of the Impressionist dictates, entirely personal and capable of overturning everything that had been done up to then.

It was 1900, the dawn of a new century, and the Picasso cyclone had arrived in Paris.

The text quoted in this post was written by Vincenzo Sanfo on the occasion of the exhibition Gli Impressionisti tra sogno e colore on show at Museo Nazionale di Artiglieria, Mastio della Cittadella – C.so Galileo Ferraris, Turin. From 11 March to 4 June 2023