Fortuny Venezia @Fotografie di Massimo Listri

Who was Mariano Fortuny, the artist who was an accomplished stylist but also a renowned designer? He was decidedly multifaceted, this Spanish artist who decided to live in Venice and who went on to conquer the world from his amazing house-museum.

Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo was born in Granada, at the foot of the Alhambra, on 11 May 1871, the second son of Mariano Fortuny y Marsal (1838-1874), acclaimed Spanish painter, and Cecilia de Madrazo y Garreta (1846-1932), daughter of Federico de Madrazo y Kuntz (1815- 1894), director of the Prado Museum.

Who was Mariano Fortuny: artist, stylist and designer

Fortuny Venezia @Fotografie di Massimo Listri

The untimely death of his father induced his mother Cecilia to reside with the family in Paris, where Mariano spent a happy childhood under the attentive guidance of his grandfather and maternal uncle Raimundo de Madrazo y Garreta (1841-1920), stimulated by the proximity of well-known men of letters, musicians, artists and scientists who frequented their home. However, what attracted Mariano Fortuny most was the revelation of a new world: that of the theatre intended for the staging of spectacular balls.

FROM PARIS TO VENICE

In 1889, his mother Cecilia decided to move the family to Venice to Palazzo Martinengo on the Grand Canal. Right from the start, the new residence was a meeting place for artists and writers: Isaac Albéniz, Martín Rico, José María Sert, José María de Heredia, Ignacio Zuloaga and, later, Marcel Proust, Reynaldo Hahn, Henri de Régnier and Paul Morand.

Mariano progressed in his studies of painting by practising, as tradition dictates, copying from the great Venetian masters, deepening his technical research into colour mixtures and the engraving arts. At the same time, already revealing his eclecticism, he cultivated equal interests in music, theatre and photography.

LIFE OF MARIANO FORTUNY BETWEEN ART, DANCE, MUSIC AND THEATRE

Beginning in 1891, following a trip with his family to Bayreuth, he began a cycle of paintings and engravings dedicated to Wagnerian themes. He also intensified his contacts with Venetian artistic circles and frequented the intellectual environment that would soon lead to the establishment of the Venice International Art Exhibition. The famous Art Biennale.

Among his acquaintances were: Cesare Laurenti, Ettore Tito, Antonio Fradeletto, Pietro Selvatico, Pompeo Molmenti, Mario De Maria and Angelo Conti. It was the latter, an official of the Fine Arts, who made a passionate and decisive contribution to Mariano’s ‘ideal’ training. Also in Venice, in 1894, Fortuny met another figure who would play an important role in his artistic life: Gabriele d’Annunzio.

In 1896 he sent the painting Garden Ornaments and Smelling Spirits, more commonly known as Flower Maidens, inspired by the second act of Parsifal and influenced, as Fortuny himself recalled in a manuscript, by memories of watching a ballet by the American dancer Loïe Fuller, to the 7th International Munich Exhibition. In Venice he made friends with the writer Ugo Ojetti, Baron Giorgio Franchetti, Prince Fritz Hohenlohe-Waldenburg, Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Eleonora Duse.

In those years, Mariano devoted himself to activities that were very congenial to him, in a continuous alternation of interests, always hovering between painting, lighting and set design. In 1899, the Venetian Countess Albrizzi entrusted him with the production of the scenic part of an operetta that was very popular at the time, Mikado, to be performed in her private theatre. Giuseppe Giacosa, Puccini’s famous librettist, in turn suggested he prepare the sketches for Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, an opera that would be performed for the first time in Italy at La Scala in Milan in 1900.

Fortuny Venezia @Fotografie di Massimo Listri

MARIANO FORTUNY’S HOME-WORKSHOP

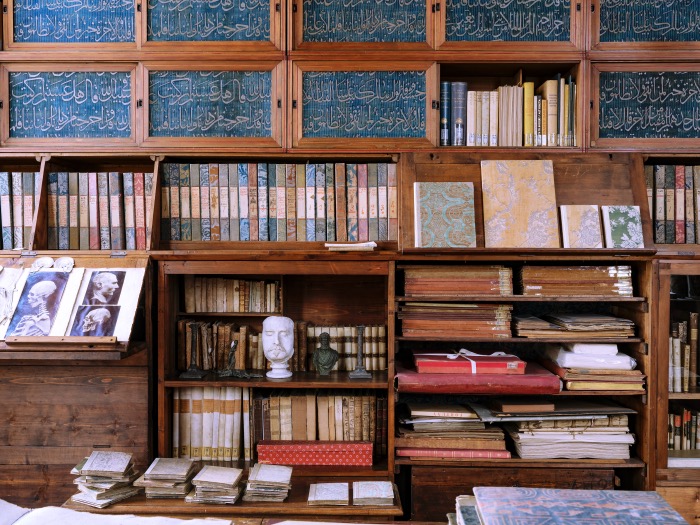

In Venice, between 1899 and 1906, Mariano took possession of the Palazzo Pesaro degli Orfei, the current Fortuny Museum, which over the years became first a workshop and then his permanent residence. It was here that the essential ideas of his complex theatrical reform were born, starting from an analytical reflection on the quality and nature of light, as well as the unexpressed technical potential in the field of stage lighting.

LIGHTING AND FASHION IN THE WORKS OF MARIANO FORTUNY

For a short period, in 1902 Fortuny rented a studio in Paris, where he devoted himself to the construction of lighting fixtures, the design of a scenographic device, the ‘Dome’, and the development of a more complex and articulated system for stage lighting with indirect light. Among the admirers who visited the Parisian studio were the actor Coquelin Aîné, Sarah Bernhardt, the playwright Victorien Sardou, the Wagnerian stage designer Friedrich Kranich, the theatrical theorist Adolphe Appia and the esotericist Joséphin ‘Sar’ Peladan.

Returning to Venice, he set up a cloth-printing workshop with Henriette Nigrin (1877-1965), his companion since their meeting in Paris in 1902.

All his work took place in Mariano Fortuny’s Venetian home, which also became a workshop and meeting place for the intellectuals and creative people of the time.

Mariano made some women’s stage costumes with this technique and, in 1906, the curtain for the private theatre of the Countess of Béarn. Large silk veils that almost completely envelop the body, worn in the manner of the women of Tanagra, printed with decorative motifs inspired by Cretan and Minoan art, are the prototypes of those later known as Knossos shawls; on 24 November 1907, at the Hohenzollern-Kunstgewerbehaus in Leipzigerstrasse in Berlin, Fortuny presented fifteen models of these.

These delicate and light creations were praised on the occasion by the greatest German-language poet of the time, his friend Hugo von Hofmannsthal.

Having momentarily abandoned painting, which in the years to come would no longer find the happy experience of the turn of the century in its subjects and execution technique, Fortuny meticulously directed his studies towards pigments, and not only for textile applications, broadening the colour ranges and employing exotic colours obtained from organic materials.

THE PATENT FOR THE PLEATED FABRIC

In June 1909, he filed a patent at the Office National de la Propriété Industrielle in Paris for the silk pleated fabric, a result obtained by means of an apparatus of his own invention; the following November he registered a patent for a tunic, a prototype of a dress that he would convert into a women’s silk robe of Hellenistic inspiration: Delphos.

The brainchild of Henriette, it was this garment that consecrated Fortuny’s international success. Actresses such as Eleonora Duse, Sarah Bernhardt and Gabrielle Réjane, dancers such as Isadora Duncan or Ruth St. Denis, noblewomen such as the Marquise de Polignac, the Empress of Germany and the Queen of Romania, femmes fatales such as the Marquise Casati wore Mariano’s clothes on stage and in life.

The production of the Orfei’s workshop in Palazzo Pesaro, which in the meantime had become a real factory with more than a hundred workers, became imposing and the need for the artist to open a commercial space became pressing: in 1912 he opened a first boutique in rue de Marignan in Paris and later in Old Bond Street in London.

The outbreak of the First World War, however, placed Mariano’s business in serious difficulty, and he was forced to severely reduce the staff of the cloth factory, perceiving the looming threat to his commercial and artistic interests. Added to this dramatic situation was the distress of his mother and sister Maria Luisa (1868-1936) who, pressurised by mortgages on Palazzo Martinengo, were forced to put part of their collection of antique textiles up for sale.

FORTUNY JOINT-STOCK COMPANY

Once the war was over, in 1919 Fortuny began the construction of a factory for the exclusive production of printed cottons on the island of Giudecca, on the San Biagio quay, on land owned by an enlightened entrepreneur who would become his partner, Gian Carlo Stucky. Having deposited the articles of incorporation of the joint-stock company called Società Anonima Fortuny with the Venice Chamber of Commerce, Mariano took over its technical and artistic direction and infused it with all his knowledge, also planning the construction of two textile printing machines.

After three years of intense work, with the start of production in August 1922, the first printed fabrics saw the light and left the Giudecca workshop to arrive on the tables of the most renowned ateliers and boutiques in Europe and America. His interest in theatrical reform did not wane and, in collaboration with the Società Anonima Leonardo da Vinci in Milan, he began a project to install the ‘Cupola’ for the Teatro alla Scala. Fortuny’s friendship with artistic director Luigi Sapelli, aka Caramba, and the esteem in which he is held by the Milanese theatre induced its management to approve the project, which, after a long gestation period, saw the light on 7 January 1922 with the performance of Richard Wagner’s Parsifal.

THE SUCCESS OF MARIANO FORTUNY

In Venice, in 1922, the Spanish Pavilion of the Biennale opened and Fortuny, in addition to exhibiting some of his works and decorating the rooms, was called to hold the position of commissioner, a position he would hold until the 1942 Biennale. In 1924 he was conferred the title of honorary consul in Venice by the King of Spain. The following year he travelled to Spain where his lamps illuminated the rooms of an exhibition of Trajes regionales in Madrid; he continued his journey by going to his home town, Granada, then to Morocco.

That same year at the Teatro Goldoni in Venice, where Emma Gramatica’s company staged George Bernard Shaw’s St Joan, Fortuny supplied printed silk velvet fabrics for the costumes and stage decoration. Those were very happy years, marked by many successes, and the general literary public also became acquainted with Fortuny’s name following the publication by Gallimard of Albertine disparue by Marcel Proust, part of the great À la recherche du temps perdu cycle.

THE LAST PART OF MARIANO FORTUNY’S LIFE

Dark shadows hung over Fortuny’s life in 1929: the international stock market crisis also affected Fortuny’s textile activities. Amidst ups and downs, he was once again present at the 17th Biennale with three works; in March 1931, he went to Paris to file a patent for a carbon pigment photographic paper of his own invention; he marketed the colours he had created and used since the beginning of his painting activity; he was invited to supply his precious fabrics and to design Othello’s dress for William Shakespeare’s play of the same name, which was to be performed in the courtyard of the Doge’s Palace in Venice in August 1933.

In 1937 Mariano again dedicated himself to lighting systems on the occasion of the great Tintoretto exhibition in Venice: his indirect and diffused lamps illuminated the rooms of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, as well as Titian’s Assumption altarpiece in the Frari church and Carpaccio’s painting cycle in the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni. The last major public engagement was the preparation of the costumes for the Triumphs of Savoy, a historical re-enactment in honour of the Prince of Naples, which took place at the Castello Sforzesco in Milan on 9 June of that year: more than eight hundred costumes were made from fabrics provided by Fortuny.

Mariano Fortuny wished to donate Palazzo Pesaro degli Orfei to his home country, but the Spanish government, after years of indecision, refused for financial reasons. Seriously ill, in September 1948 Mariano drafted his will in which he stated:

“I leave to my wife everything I own, inherited, bought, produced, furniture and real estate, everything without exception”.

Mariano Fortuny died in his Venetian home on 2 May 1949. Wrapped in a habit as Spanish tradition dictated, his remains, after the funeral attended by family, close friends and public authorities, were transferred to Rome’s Verano Cemetery, next to those of his famous parent.